|

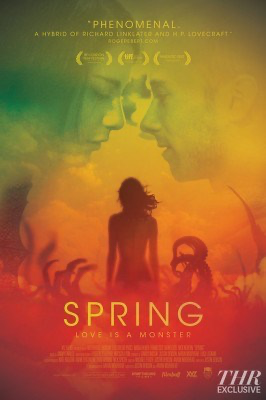

Today I provide my thoughts on Benson and Moorhead’s Spring, which I reviewed for SF Signal a couple of years ago. You can read my review here. I provide the text below. Calling a movie unconventional often suggests that it either is an experiment that ultimately fails or plays with some aspect of genre or medium while remaining traditional at heart. And yet unconventional best describes Spring, an unusual romance written by Justin Benson and directed by Benson and Aaron Moorhead, and this poses a challenge to one who wishes to talk about it. Yes, one might look at it as an experiment; in this case, a mix of genres that threatens to clump together into a misshapen blob reeking of celluloid sludge, yet somehow finds the right covalent bonds, thus transforming the divergent elements into a unified compound. Or one might see it as a very traditional tale of star-crossed lovers woven with threads of science fiction and horror, creating an attractive (if not always seamless) blend. However one views it, Spring draws its viewer in while upending expectations. It opens on a grim note, setting the stage for what might, at first glance, be a simple study of twentysomething angst and loss. Evan (Lou Taylor Pucci), in mourning after his mother’s death, embroils himself in a barroom fight that causes him to flee the country. These sequences surprise because of their frankness (Pucci plays Evan’s care for his mother with the right amount of tenderness and sorrow) and honesty (the fight that erupts in the bar jars with its suddenness and Evan’s anger), though his decision to flee after the other party calls the police seems somewhat out of character. We expect this opening in a standard independent movie, not a genre picture. With nowhere else to go and with no family obligations, he travels to Italy, where he enjoins a pair of young British tourists as they carouse across the country’s more scenic locales. He meets Louise (Nadia Hilker) and they share an immediate mutual attraction. When his British friends decide to move on, Evan stays behind to work as a farm hand and begin a romance with Louise, who describes herself as “half undiscovered signs, a bunch of confusing biochemistry, and some crazy hormones.” It intrigues the aimless Evan, though he maintains his own boundaries (“I have to know that you’re the kind of crazy I can deal with,” he tells Louise) as she lays their relationship’s ground rules: he can only see her at night, and he cannot tell anybody about their nights together. It sets the stage for horror—and certain scenes suggest that Spring actually rests firmly in this camp—yet the tone never slips fully into all-out horror mode. When Evan asks Louise about the syringes he finds in her apartment, she explains that she has an intermittent medical condition (“It’s a very long story,” she tells him), it only increases his interest and concern. He falls in love (it wouldn’t be a love story otherwise). She attempts to break up with him, stating that she does not believe him ready for where their relationship is going. And then… Divulging what Evan learns enters into spoiler territory, unfortunately, because what follows upends what otherwise would dip into standard horror fare. Louise possesses a secret (one that Benson and Moorhead cleverly foreshadow by focusing each scene’s opening on an animal), but Evan handles the revelation not with horror but curiosity. A monstrous transformation occurs and delivers the shock one would hope, but it avoids the standard creatures one almost can set the rising of the full moon by. And then the even more surprising thing happens: the love story continues, simply incorporating this new data into the narrative, a trick readers of Lucius Shepard’s tales of expatriates encountering magic on alien shores might recognize. (Indeed, a part of me could not help but think of Spring as the best story based on Shepard’s work that never focused on a specific story.) Wisely, Benson and Moorhead maintain their focus on their characters, drawing them with more depth than in typical genre material, yet never with the self-consciousness that informs far too much independent cinema. Pucci and Hilker help them by digging deeply into their characters, breathing life into people who might otherwise have dipped into cliché. They also create unease through tension of tropes that work together far better than they should, and evoke effective symbols that, at times, might appear too literal, as when flowers either bloom or wither in Louise’s presence. They serve a symbolic purpose, but also function as a reaction to Louise herself. With everything Spring gets right, it missteps at the end by running a second or two too long. It must end with Louise torn between love and her confusing biochemistry, and does so. Perhaps Benson and Moorhead couldn’t quite trust the audience with the material, and so decided to make Louise’s choice explicit. Ending just the tiniest bit sooner would have strengthened the movie. Fortunately, it harms none of what came before, and provides the movie with some closure. Spring might lack perfection, but like the season it titles itself after, brims with promise.

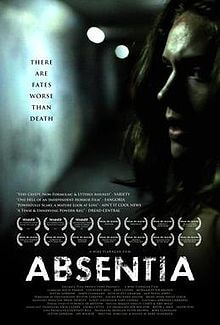

It’s the not knowing that causes the most pain. This is why it takes so long to accept that our missing loved ones might be dead. It’s been seven years since the disappearance of Tricia’s (Courtney Bell) husband Daniel, an event she finally has decided to accept, and she prepares to declare him dead in absentia. Her sister Callie (Katie Parker), a former addict, appears at her Glendale home and stays with her as they file Daniel’s death certificate and seek a new home for Tricia. Tricia suffers nightmares. Her doctor interprets them as stress and guilt. One morning Callie jogs. In a tunnel she meets Walter Lambert (Doug Jones), gaunt from hunger and surprised that she can see him. Walter begs her to contact his son. She runs away but returns with food. The tunnel is empty. Later, Callie discovers a pile of metal objects on Tricia’s doorstep and assumes Walter left them. She places them at the tunnel entrance, where a man depositing a trash bag in the same location warns her not to leave them. When Callie investigates later, she learns that Walter was declared dead in absentia several years ago, and that his son claims he was taken away by monsters. The objects show up in Callie’s bed. Detective Ryan Mallory (Dave Levine) arrives when Callie calls the police and chastises her and Tricia for keeping their door unlocked. (It turns out that Mallory and Tricia have begun a relationship). Anxious, Callie relapses into drug use as Tricia finally signs Daniel’s death certificate. As she prepares to enjoy a date with Mallory, Daniel appears in front of their apartment. Bloody, barefoot, and severely malnourished, he tells them that he has been “underneath,” and expresses terror at the mouth of the tunnel near Tricia’s house. Writer and director Mike Flanagan keeps Absentia’s premise small, but its scale allows the movie incredible tension as it progresses. It helps that he initially avoids shooting the picture as a horror movie, opting instead for natural lighting and a drab color palate. He extends this naturalism to his actors, who strive for an ordinariness that borders on routine. Parker especially is good as Callie; she is not Kathy from The Monster, but someone whose life was overtaken by addiction and is now trying to get better. One could almost mistake Absentia for an adaptation of a Raymond Carver story as viewed by Dogma 95 hangers-on, especially during the first scenes when Tricia and Callie reunite. Such things catch Absentia’s audience off guard. Better still, Flanagan only turns up the horror atmosphere by degrees, even when the first dreams frighten Tricia; like a frog in a pot slowly boiling, the characters do not realize what kind of picture they are in until late in the movie.

Absentia surprises, too, by incorporating elements of Lovecraftian cosmic horror. For a movie that maintains its focus on quiet, emotional elements, the inclusion of something supernatural might seem out of place. But Flanagan incorporates all of these elements into a well-constructed tale, and never loses sight of his characters. I’m at the point in this story where I am screaming, “What the f*ck am I doing?! I am putting my name on this piece of sh*t!”

On their surface, the events of The Invitation (2015) unfold in an unremarkable, even mundane, fashion. A couple hosts a dinner party in a modern, upscale home somewhere in California (where screenwriters Phil Hay and Matt Manfredi never state) after secluding themselves for over two years. One of the guests (Will, played by Logan Marshall-Green) used to be married to Eden (Tammy Blanchard), one of the hosts, so we think we understand his discomfort in attending. Only as the movie progresses do we learn more: their son Ty was killed in an accident, causing their marriage to fall apart. Eden now lives with David (Michiel Housman), whom she met in a grief support group. Before Will and his new girlfriend Kira (Emayatzy Corinealdi) arrive at Will’s and Eden’s former home, however, Will strikes a coyote with his car. The animal survives but is mortally wounded, leaving little choice but to kill it out of mercy. The scene allows director Karyn Kusama to suffuse the movie with the menace and dread undercutting the gathering. Will and Kira arrive, as do others. David and Eden introduce Sadie (Lindsay Burdge), a woman they met while in Mexico and who stays with them. Her wide eyes and sudden movements suggest past trauma. More friends show up, including Pruitt (John Carroll Lynch), whom the guests have never met. They play games, and David and Eden tell everyone about a group to which they, Sadie, and Pruitt belong. Called “The Invitation,” it works through grief using a New Age–style spiritual philosophy. The friends joke that the couple has joined a cult, and some grow uneasy when David and Eden play a video of the Invitation’s leader comforting a dying woman. Ultimately, they laugh it off. Will does not. He notices that David keeps the front door locked. When he steps outside for firewood he spies Eden through her bedroom window, hiding a pill bottle. He expresses his unease, especially when Pruitt accompanies one of the guests back to her car. David confronts Will, claiming that he is suspicious. As dinner is served, Will’a memories of Ty and Eden add to his growing paranoia.

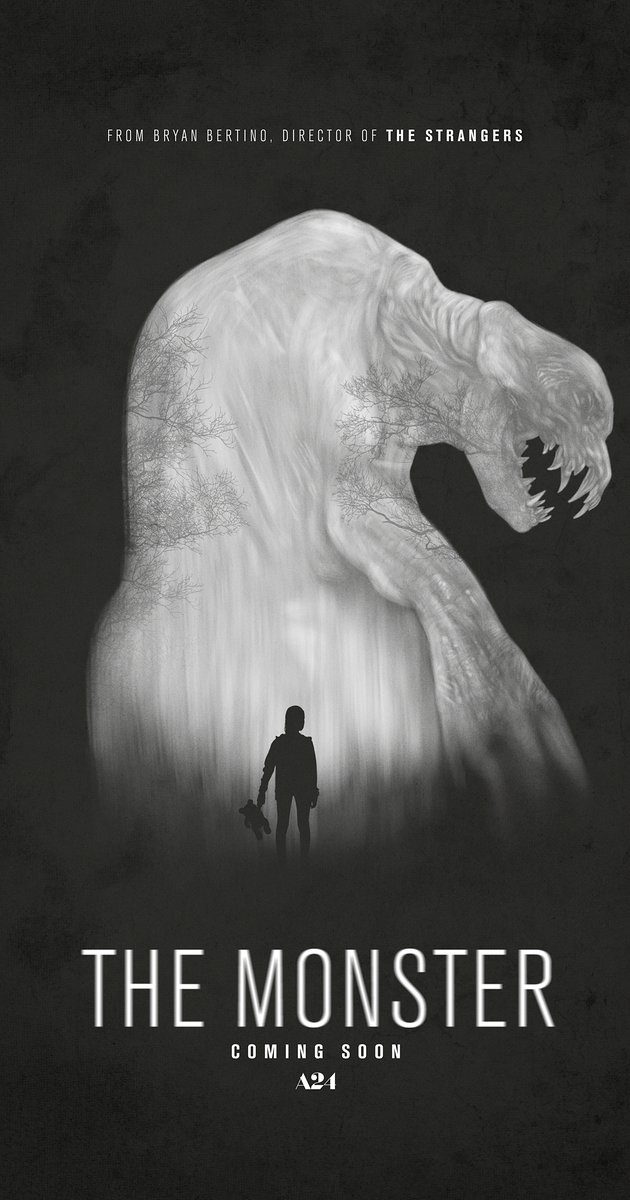

As with most strong thrillers, The Invitation works by keeping the viewer off balance; I kept thinking of Dennis Etchison’s suburban nightmares throughout, the sense that this normal gathering is not at all normal. Kusama offers visual cues of what will unfold but also keeps David’s and Eden’s explanations logical enough that we wonder if Will’s grief is causing him to misread events. In addition, Kusama also keeps the movie’s focus almost exclusively on Will, which only adds to the movie’s air of danger. Therefore, though the movie demands a good ensemble cast (and has one), the weight of the picture rests on Marshall-Green’s shoulders, requiring detachment that masks his powerful loss. Blanchard and Huisman, too, must walk a delicate dramatic tightrope; their tender, understanding smiles obfuscate their true intentions, and they both pull it off with remarkable ease. Yes, what could have been a meditation on how people change in the face of grief instead opts instead to be an efficient, nail-biting exercise in suspense, but it does so with great skill. If, as Harlan Ellison writes, the monsters that live within our skins are the worst, then horror allows us to examine those monsters in a metaphorical context. Few people enjoy horror for this reason. It externalizes the worst parts of our humanity and explores the destruction we inflict on others and on ourselves. Most refuse to acknowledge that monsters exist at all; others distance themselves by claiming some of us are free of them, or that we do not need the symbolism. At their best, horror fiction and film state otherwise, and it is part of what makes a lean chiller like The Monster so effective. What is more terrifying: the monster trapping you in an enclosed space, or the one within your body clawing its way out? Kathy (Zoe Kazan) knows her own monster. Alcoholism has frayed her relationship with her ten-year-old daughter Lizzy (Ella Ballentine). Tired of acting as Kathy’s caregiver, Lizzy decides she wants to live with her father permanently and will inform him of this decision on her next visit. Kathy drives Lizzy to her father’s house, but they hit a wolf along the way, and discover that its wounds are not just from the accident but also from what looks like an animal. Their own car damaged, Kathy contacts a tow truck; when it arrives, Lizzy sees that the dead wolf has vanished. And then something attacks the tow truck driver, forcing Kathy and Lizzy to hide in their damaged car and wait for other help to arrive. As with Honeymoon (2014), which I discussed yesterday, writer/director Bryan Bertino generates considerable tension from his simple setup, keeping the focus almost exclusively on Kathy and Lizzy and only occasionally leaving the car in which they are trapped. Kazan plays Kathy as we often think we know addicts: self-absorption brought about by relentless victimization, bitter about her position yet powerless to leave it, trapped in a codependent relationship with a child she needs but finds difficult to love. Ballentine avoids contrasting Lizzy as blameless, portraying her instead as angry, resentful, but with an undercurrent of love. In the hands of other actors, such volatile dynamics would tip the movie into hysterical melodrama, and almost do at the beginning, but Kazan and Ballentine find the right footing by the time they begin their journey. Their animosity, cultivated by years of disappointment and hostility, feels real, rather than a horror movie contrivance, lending authenticity and real drama to the story. I realize that I have not written about the monster itself, a creature that reminds one of Giger’s creature design in Alien merged with a giant reptile. Impressive and terrifying as it is (to say nothing of memorable), it sticks less in one’s memory than the two trapped characters. The monster’s phallic appearance suggests a commentary on gender roles, and a case could be made for such, as the rescuers (such as they are) seem ineffectual. But The Monster shows almost no interest in this particular subtext. The monster in question is Kathy’s addiction made manifest, and the damage it has caused both her and her daughter. Yes, the monsters that live within our skins are the worst, and confronting them is terrifying. But we must confront them, or they will consume us.

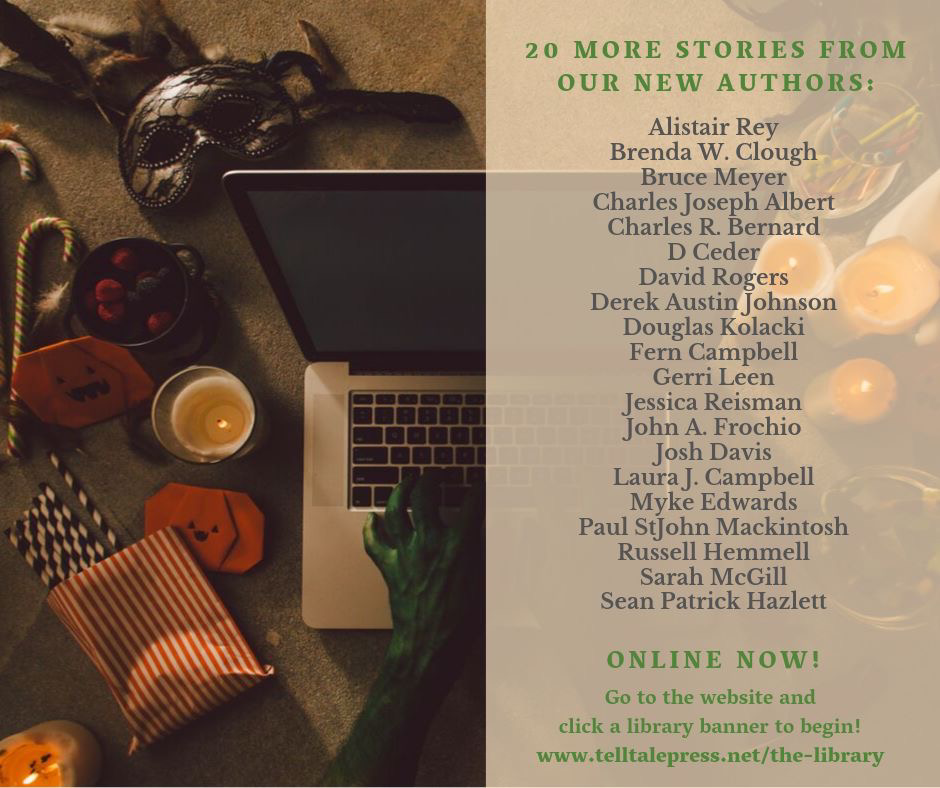

And now a public service announcement from Tell-Tale Press. I’ll provide a link to my story when it becomes available.

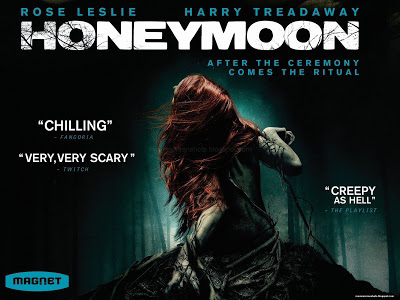

Sometimes we miss the point of horror. We forget that we can find the most terrifying moments in the simplest premises. Certainly this is the case with Honeymoon, the 2014 feature by first-time director Leigh Janiak. One might yawn at the familiarity of its scenario, but to do so would be to dismiss an elegant, terrifying tale about how little we know about the people we love, and how powerless we are when their mask slips. Newlyweds Bea (Rose Leslie) and Paul (Harry Treadaway) arrive at a secluded cabin for their honeymoon. They go to a small restaurant where the owner Will (Ben Huber) asks them to leave before Will realizes that he is Bea’s childhood friend. Will’s wife joins them, and tells Bea and Paul that they need to leave. Shortly after this encounter, Bea leaves the cabin in the middle of the night. Paul finds her naked and disoriented in the woods. She claims she was sleepwalking. “Stress,” she explains. Their honeymoon continues, but Bea’s behavior becomes even more strange. Honeymoon unsettles from the opening frames. Home movies of Bea’s and Paul’s wedding show a joy muted by...something. The story of their first date and Paul’s proposal ought to be a typical Meet Cute, but from the beginning what appears to be romantic feels uncanny and off. As the movie progresses, events unnerve Paul. Bea turns emotionally distant, and Paul initially blames their meeting with Will before realizing that some other factor is at play. One night, Paul awakens to bright lights shining through the cabin’s bedroom windows but sees nothing when he investigates. Bea behaves more erratically, and Paul notices marks on her inner thigh. “Mosquito bites,” she tells him. To say more would give away Honeymoon’s remarkable gems. Janiak generates good suspense from the screenplay (co-written with Phil Graziadei) and through impressive sound design. It builds slowly, with events that suggest one thing but diverge when when we think we know where the movie is going. Good too is Janiak’s use of atmosphere; shadows creep from the Canadian woods surrounding the cabin, filling the idyllic location with foreboding. The cabin itself invites at first glance before folding over its inhabitants.

Character-driven movies fail without strong casting. Fortunately, the leads stand out. Treadaway and Leslie work well together, evoking intimacy and love that turns to dread, anxiety, and terror in an all-too-believable manner. It helps, too, that Honeymoon maintains its focus on Paul’s point of view. We learn things as he does, which deepens the mystery. I do wish Janiak and Graziadei provided a more satisfying ending. It makes sense within the logic of the story, and it arrests in its final shots, but it also leaves the viewer with more questions than answers. Perhaps the questions are the point. Who is the person you love, really? Do you know them? Are you sure? For this Halloween month, I want to try something a little different.

Every year, my friend Mark Finn offers his top five master horror list. It’s always enjoyable, and always is worth your time. With stories to complete and a novel to finish I do not have the time to do exactly the same thing. But I would like to offer capsule reviews of horror movies you might enjoy this Halloween season. I’m proposing one review per day of non-classic horror movies. Why non-classic? Because we know and have seen the classic ones many times over. We’ve all seen The Exorcist. We’ve seen Night of the Living Dead. We’ve seen Halloween and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Friday the 13th and so many others. But horror encompasses more than these well-known titles, work that is worth your time. Things that you might have scrolled by on your streaming service of choice and thought might be interesting but might have forgotten to search for again. I’ll try to keep my reviews and recommendations to those streaming, but if you find them on DVD or blu-ray I’d recommend picking them up. 31 movies. 31 days. Those who are up for it can find my first selection later today. |

Derek Austin Johnson has lived most of his life in the Lone Star State. His work has appeared in The Horror Zine, Rayguns Over Texas!, Horror U.S.A.: Texas, Campfire Macabre, The Dread Machine, and Generation X-ed. His novel The Faith was published by Raven Tale Publishing in 2024.

He lives in Central Texas. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed