|

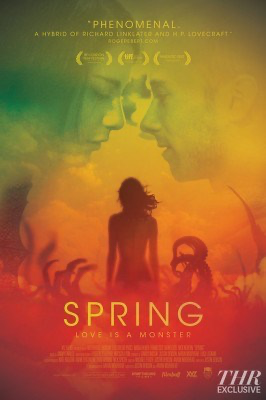

Today I provide my thoughts on Benson and Moorhead’s Spring, which I reviewed for SF Signal a couple of years ago. You can read my review here. I provide the text below. Calling a movie unconventional often suggests that it either is an experiment that ultimately fails or plays with some aspect of genre or medium while remaining traditional at heart. And yet unconventional best describes Spring, an unusual romance written by Justin Benson and directed by Benson and Aaron Moorhead, and this poses a challenge to one who wishes to talk about it. Yes, one might look at it as an experiment; in this case, a mix of genres that threatens to clump together into a misshapen blob reeking of celluloid sludge, yet somehow finds the right covalent bonds, thus transforming the divergent elements into a unified compound. Or one might see it as a very traditional tale of star-crossed lovers woven with threads of science fiction and horror, creating an attractive (if not always seamless) blend. However one views it, Spring draws its viewer in while upending expectations. It opens on a grim note, setting the stage for what might, at first glance, be a simple study of twentysomething angst and loss. Evan (Lou Taylor Pucci), in mourning after his mother’s death, embroils himself in a barroom fight that causes him to flee the country. These sequences surprise because of their frankness (Pucci plays Evan’s care for his mother with the right amount of tenderness and sorrow) and honesty (the fight that erupts in the bar jars with its suddenness and Evan’s anger), though his decision to flee after the other party calls the police seems somewhat out of character. We expect this opening in a standard independent movie, not a genre picture. With nowhere else to go and with no family obligations, he travels to Italy, where he enjoins a pair of young British tourists as they carouse across the country’s more scenic locales. He meets Louise (Nadia Hilker) and they share an immediate mutual attraction. When his British friends decide to move on, Evan stays behind to work as a farm hand and begin a romance with Louise, who describes herself as “half undiscovered signs, a bunch of confusing biochemistry, and some crazy hormones.” It intrigues the aimless Evan, though he maintains his own boundaries (“I have to know that you’re the kind of crazy I can deal with,” he tells Louise) as she lays their relationship’s ground rules: he can only see her at night, and he cannot tell anybody about their nights together. It sets the stage for horror—and certain scenes suggest that Spring actually rests firmly in this camp—yet the tone never slips fully into all-out horror mode. When Evan asks Louise about the syringes he finds in her apartment, she explains that she has an intermittent medical condition (“It’s a very long story,” she tells him), it only increases his interest and concern. He falls in love (it wouldn’t be a love story otherwise). She attempts to break up with him, stating that she does not believe him ready for where their relationship is going. And then… Divulging what Evan learns enters into spoiler territory, unfortunately, because what follows upends what otherwise would dip into standard horror fare. Louise possesses a secret (one that Benson and Moorhead cleverly foreshadow by focusing each scene’s opening on an animal), but Evan handles the revelation not with horror but curiosity. A monstrous transformation occurs and delivers the shock one would hope, but it avoids the standard creatures one almost can set the rising of the full moon by. And then the even more surprising thing happens: the love story continues, simply incorporating this new data into the narrative, a trick readers of Lucius Shepard’s tales of expatriates encountering magic on alien shores might recognize. (Indeed, a part of me could not help but think of Spring as the best story based on Shepard’s work that never focused on a specific story.) Wisely, Benson and Moorhead maintain their focus on their characters, drawing them with more depth than in typical genre material, yet never with the self-consciousness that informs far too much independent cinema. Pucci and Hilker help them by digging deeply into their characters, breathing life into people who might otherwise have dipped into cliché. They also create unease through tension of tropes that work together far better than they should, and evoke effective symbols that, at times, might appear too literal, as when flowers either bloom or wither in Louise’s presence. They serve a symbolic purpose, but also function as a reaction to Louise herself. With everything Spring gets right, it missteps at the end by running a second or two too long. It must end with Louise torn between love and her confusing biochemistry, and does so. Perhaps Benson and Moorhead couldn’t quite trust the audience with the material, and so decided to make Louise’s choice explicit. Ending just the tiniest bit sooner would have strengthened the movie. Fortunately, it harms none of what came before, and provides the movie with some closure. Spring might lack perfection, but like the season it titles itself after, brims with promise.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Derek Austin Johnson has lived most of his life in the Lone Star State. His work has appeared in The Horror Zine, Rayguns Over Texas!, Horror U.S.A.: Texas, Campfire Macabre, The Dread Machine, and Generation X-ed. His novel The Faith was published by Raven Tale Publishing in 2024.

He lives in Central Texas. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed