|

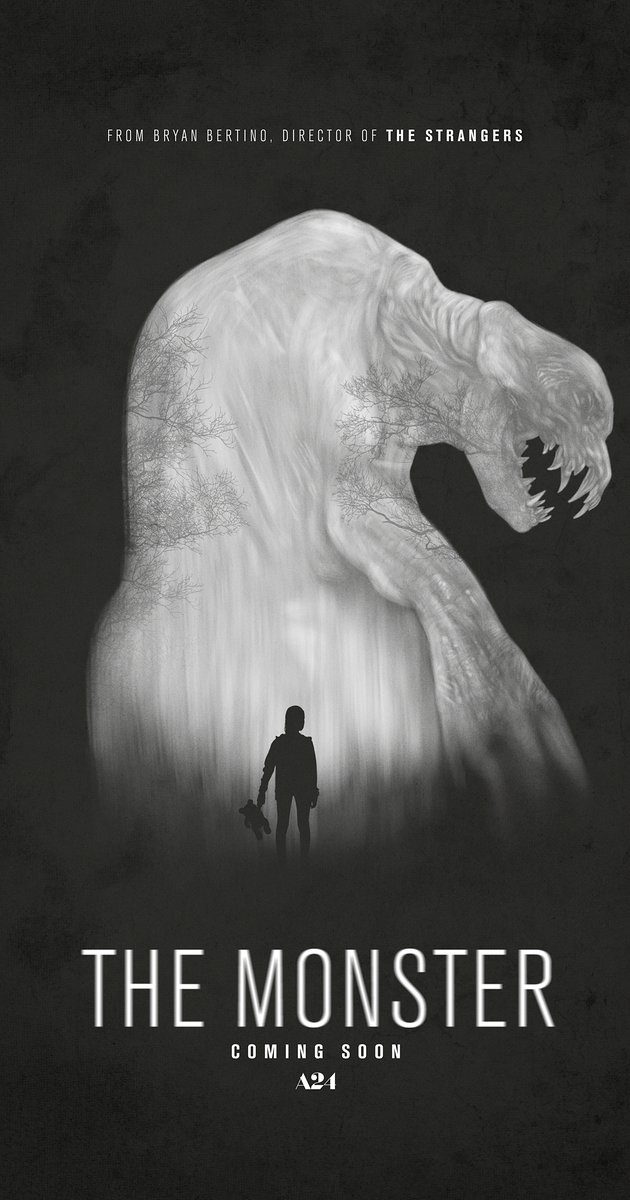

If, as Harlan Ellison writes, the monsters that live within our skins are the worst, then horror allows us to examine those monsters in a metaphorical context. Few people enjoy horror for this reason. It externalizes the worst parts of our humanity and explores the destruction we inflict on others and on ourselves. Most refuse to acknowledge that monsters exist at all; others distance themselves by claiming some of us are free of them, or that we do not need the symbolism. At their best, horror fiction and film state otherwise, and it is part of what makes a lean chiller like The Monster so effective. What is more terrifying: the monster trapping you in an enclosed space, or the one within your body clawing its way out? Kathy (Zoe Kazan) knows her own monster. Alcoholism has frayed her relationship with her ten-year-old daughter Lizzy (Ella Ballentine). Tired of acting as Kathy’s caregiver, Lizzy decides she wants to live with her father permanently and will inform him of this decision on her next visit. Kathy drives Lizzy to her father’s house, but they hit a wolf along the way, and discover that its wounds are not just from the accident but also from what looks like an animal. Their own car damaged, Kathy contacts a tow truck; when it arrives, Lizzy sees that the dead wolf has vanished. And then something attacks the tow truck driver, forcing Kathy and Lizzy to hide in their damaged car and wait for other help to arrive. As with Honeymoon (2014), which I discussed yesterday, writer/director Bryan Bertino generates considerable tension from his simple setup, keeping the focus almost exclusively on Kathy and Lizzy and only occasionally leaving the car in which they are trapped. Kazan plays Kathy as we often think we know addicts: self-absorption brought about by relentless victimization, bitter about her position yet powerless to leave it, trapped in a codependent relationship with a child she needs but finds difficult to love. Ballentine avoids contrasting Lizzy as blameless, portraying her instead as angry, resentful, but with an undercurrent of love. In the hands of other actors, such volatile dynamics would tip the movie into hysterical melodrama, and almost do at the beginning, but Kazan and Ballentine find the right footing by the time they begin their journey. Their animosity, cultivated by years of disappointment and hostility, feels real, rather than a horror movie contrivance, lending authenticity and real drama to the story. I realize that I have not written about the monster itself, a creature that reminds one of Giger’s creature design in Alien merged with a giant reptile. Impressive and terrifying as it is (to say nothing of memorable), it sticks less in one’s memory than the two trapped characters. The monster’s phallic appearance suggests a commentary on gender roles, and a case could be made for such, as the rescuers (such as they are) seem ineffectual. But The Monster shows almost no interest in this particular subtext. The monster in question is Kathy’s addiction made manifest, and the damage it has caused both her and her daughter. Yes, the monsters that live within our skins are the worst, and confronting them is terrifying. But we must confront them, or they will consume us.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Derek Austin Johnson has lived most of his life in the Lone Star State. His work has appeared in The Horror Zine, Rayguns Over Texas!, Horror U.S.A.: Texas, Campfire Macabre, The Dread Machine, and Generation X-ed. His novel The Faith was published by Raven Tale Publishing in 2024.

He lives in Central Texas. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed